This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

If you would have asked me a decade ago if I thought Project Based Learning would ever expand beyond a small pocket of innovative schools I would have said “I doubt it”; I could never have imagined that it would be such a widely-used buzzword in 2020. To my pleasant surprise it has expanded to mainstream vernacular and is continuing to sweep across schools in our country.

And yet, despite all the buzz surrounding it, there still is a pretty wide range of understanding as to what high quality PBL is, and more importantly, how to plan for and facilitate it. To many, PBL is met with uncertainty and apprehension; while terms used to describe PBL, like organized chaos, productive noise, and student-driven sound appealing to some, for the majority it creates a lot of unnecessary ambiguity.

To most teachers’ surprise, I like to think about PBL as a structure, almost a formula, that can both uphold academic rigor and also engage students. To show you what that structure looks like in action, I’ll walk you through how I plan a PBL lesson step by step.

Before we jump into how to approach planning a project, it’s important that we are operating from the same definition of PBL, because there are many! After years of working in the leading organizations of the PBL movement I came to arrive on the following as my non-negotiables for a project to reflect high quality PBL:

So what does it look like to put these non-negotiables into practice and plan a project? I will walk you through the process I have come to embrace and share with teachers who cross my path, either through our time together in the trenches during project coaching, or when they pick up my book, Keep it Real with PBL (for elementary and secondary). The specific project I highlight here, Silent Voices, is a collaborative effort between myself and the 5th grade team at Lake Elementary in Vista, CA.

The 5th grade team at Lake Elementary is comprised of four teachers. The team wanted to tackle a content area they knew they needed to go “deeper” with to better engage their students: The American Revolution. We knew this topic was difficult to make interesting for students, but we believed that through PBL we could successfully provide them with a rigorous, authentic and meaningful learning experience.

I often hear from teachers that getting started with a project idea is the hardest part, but for me it’s the most exciting part! I encourage teachers to identify a Driving Standard (these typically come from science or social studies because they both provide a nice context, which math or ELA can easily support). From there, think about a current issue that brings the standards to life.

Knowing they wanted to teach about the American Revolution, the teachers pulled the California social studies standards they were responsible for covering; specifically, 5.5: “Students explain the causes of the American Revolution” and 5.6: “Students understand the course and consequences of the American Revolution.”

We sat around a whiteboard and threw up a bunch of ideas that could possibly make students interested in an event from over 200 years ago. We landed on the concept of connecting hidden voices (an issue that would feel relevant to them as 10 year olds) and empathy-building (a character trait from school also familiar to them) to the historic event. We also landed on supporting standards of Common Core ELA for narrative writing, compare and contrast, and research; but more on that later!

My approach to project planning is very much rooted in Understanding by Design (UBD), so once I have identified the standards and an authentic issue, I then jump to the final product. There are so many ways students can show what they have learned—from public service announcements, to podcasts or documentaries, to art installations and simulations or performances. Whatever is decided upon, all the project planning from this point on is in service of preparing students to ultimately produce that final product.

As we continued planning this project, the teachers at Lake realized that there was SO much they could do with this concept of elevating silenced voices and building empathy awareness, that we actually had to scale back our final product ideas! Together we landed on having students create two final products:

1) 2-voice poetry, which is a style of narrative poetry that showcases the similarities and differences between two unique perspectives, or voices. Students would write and create an audio recording of the reading of their written poetry to share via listening stations at Open House Exhibition. This final product would showcase important ELA skills such as speaking and listening standards, the use of technology and writing production, and narrative writing techniques.

2) Student art: Students would represent their understanding of a “hidden voice” or silenced perspective in a contemporary issue using symbolism and a specific art style (photography, digital art, painting, or pop art). Students would also write a detailed artist statement for submission of their work to the San Diego County Fair. In this artist statement students would explain the historical and contemporary inspiration for their work, style choices, and influences; thus bringing together the social studies standards and ELA research standards (and possibly even art standards if the art teacher chose to collaborate!), using topics of student interest as the context of the product.

This is arguably the most important step because it ensures that best practices of scaffolding and formative assessment are embedded in the project. Benchmarking is simply taking your end products and breaking them down into manageable phases, or milestones. Within each of these benchmarks the teacher identifies the content and skills necessary to complete the given phase of the project. Tied to each benchmark is a concrete deliverable that students turn in to be formatively assessed. While daily checks for understanding are still happening and smaller assignments may be collected for credit, project benchmark deliverables are formatively assessed using a project rubric (more on that next!) and recorded in the grade book.

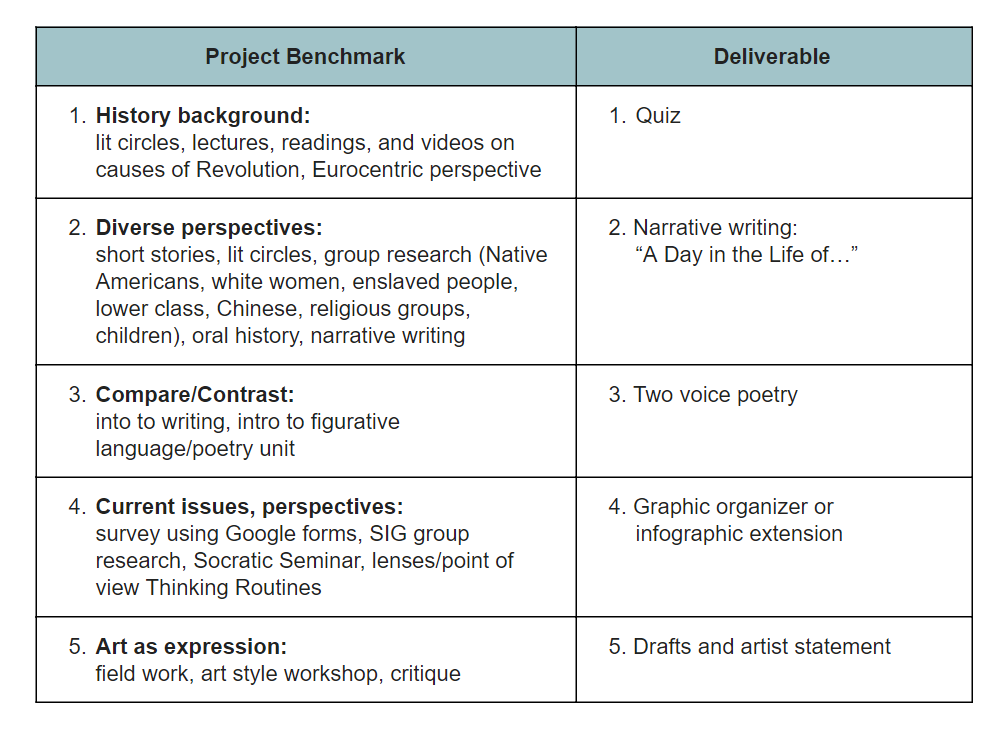

For the Silent Voices project, we identified the following benchmarks and deliverables:

In Benchmark #1 students learned about the “big picture” historical context of the American Revolution—the causes of the revolution and the early events and individuals—through textbook readings, PowerPoint lectures, videos and other short readings. The focus of these individuals and events was from a Eurocentric perspective—typical of what we would find in most textbooks. Students also began novels that represented voices of those we don’t typically hear in our textbooks: enslaved people, children, women, etc. To show that students had mastered the necessary content from this benchmark they completed a traditional history quiz. Sometimes it’s okay to include traditional assessment methods as benchmark deliverables—you don’t have to throw the baby out with the bathwater in PBL, and in these circumstances a rubric isn’t necessary for grading since the feedback and the depth of learning are limited.

Benchmark #2 focused on the experiences of the “silent voices” in the American Revolution. Teachers provided model texts through short stories of Native Americans, white women, enslaved people, lower class, Chinese, religious groups, and children. Students continued reading their literature circle novels during ELA and also learned about narrative writing techniques through writers workshop methods. The benchmark deliverable for this second section of the project was a piece of writing titled “A Day in the Life of…” which represented what daily life was like for a person from one of the groups of the “silent voices.” This deliverable showcased their narrative writing skills, textual analysis skills, and content mastery for social studies. Because the textbooks don’t provide the perspective of “the silent voices” students truly had to synthesize, analyze and apply what they were learning in ELA and social studies to be able to complete this benchmark—the higher order thinking that this project requires is one of the many reasons I love it!

Benchmark #3 required students to continue analyzing what they were learning on this topic by collaborating with a peer to find the differences and commonalities across two unique “silent voices.” Students were guided through the process by discussion protocols, visible thinking routines, completing a venn diagram, and a workshop on 2 voice poetry. Ultimately they wrote and recorded the audio for this benchmark’s deliverable, a 2 voice poem to show two different perspectives from the American Revolution. This benchmark used narrative writing techniques from the second benchmark as well.

Benchmark #4 moved students from the historical time period of the American Revolution to the current day. Throughout this benchmark students were challenged to look for the perspective of the “silent voices”—whose story are we not hearing? Students were exposed to some contemporary issues though various forms of media, conducted a survey of other students to gauge problems within their student population, engaged in more discussion protocols and ultimately landed on a topic for their own research based on their interest (Special Interest Groups-SIG). After conducting this research students created a detailed graphic organizer to show what they had collected and organized; some students chose to complete an infographic as a challenge option.

Benchmark #5: In the final benchmark students applied everything they had learned about searching for the story of “silent voices” through historical and contemporary events, and used art as the vehicle for showcasing their knowledge and skills. Each of the four teachers identified a style of art they were passionate about—photography, digital art, painting and pop art. Each teacher created a series of workshops about their art style, including well-known artists, artistic composition, and basics of color and design. Students worked with the teacher that matched their interest, analyzed models from their given style, and ultimately learned how to create a piece of work that showed the silent voices in a given current issue from their research. Students went through the critique process of drafting and also completed an artist statement with their final product—all of which was curated and exhibited for the community.

In keeping with the spirit of UBD, I also create assessment tools with the end in mind, which produces a pretty large project rubric (but never fear, we never use ALL of it at once—more on that in step 6!).

To build this rubric I encourage teachers to take the following steps:

To see what the entire project rubric looked like for the Silent Voices project, click HERE.

Once the project rubric is completed then you can begin to think about which rows will be used with which benchmarks. Each benchmark will get its own separate, smaller rubric that will only have a few standards on it. I encourage teachers to try to map it out so that each row of the larger project rubric is used twice throughout the project. The purpose of this is so that students can reflect, receive feedback and have the opportunity to grow in each area at multiple points throughout the project; this is truly assessment for learning, rather than assessment of learning. What this also means is that each benchmark will likely only be assessed using 2-3 rows from your (very large!) rubric.

You can see which rows of the rubric were used for which benchmarks in the “Silent voices” project by looking at the far left column on the project rubric (link in previous section). These benchmark numbers dictate what the smaller rubrics will look like for grading each deliverable (since, remember from my note in step 4, we will never use this entire rubric at once!). So for example, benchmark #3’s rubric would include the following rows only: collaboration, viewpoints and narrative writing.

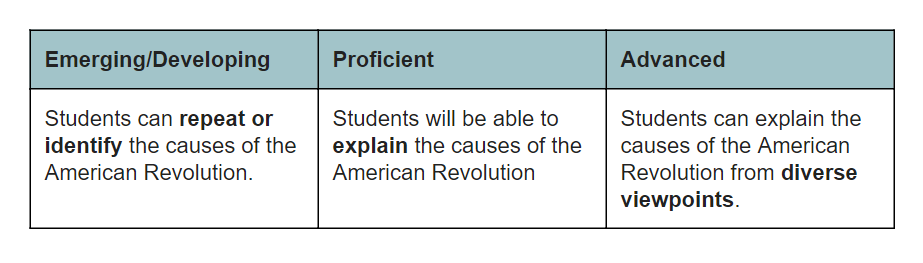

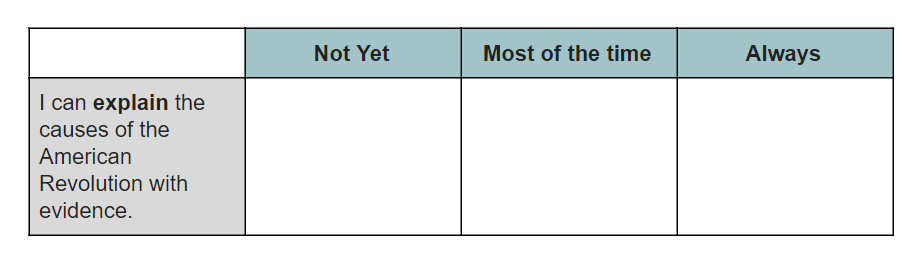

Most teachers from most grades will tell you that the language of standards are not student-friendly, and I agree! That’s why I encourage teachers to take their teacher rubric and convert it into a student rubric. To do this, simply take each row of your teacher rubric, look at the proficient box, and write the standard as success criteria for students, or “I can” statements. This breaks down teacher-facing language into vocabulary that students can understand, which helps them to know what is expected of them while also helping them reflect on their learning. Using the teacher rubric row from the above example, you can see what a row for students would look like below:

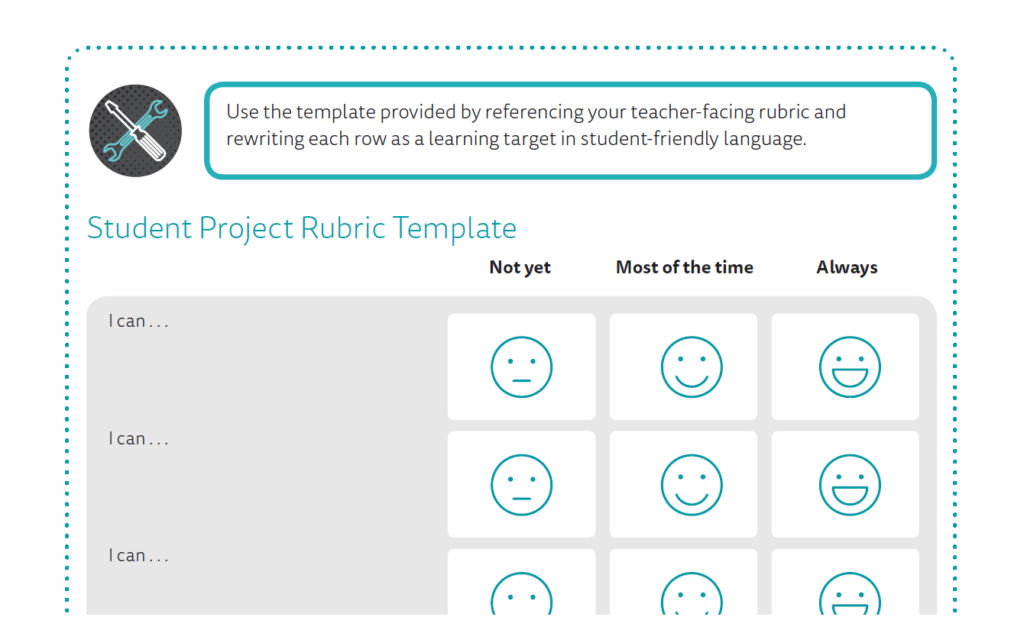

You can see a blank and completed student template in my book Keep it Real with PBL. (Teaser: it even includes emojis that elementary students love!)

Now is when ‘the rubber hits the road’ and it’s time to think about what daily learning will look like within your project. I like to simply use a Google Doc and create a table that mirrors that of a 30-day calendar, that way you can hyperlink all the daily lesson plans and resources so that it’s in one place. Most of what is linked in these Google Docs are simply workshop resources and lesson plans that teachers traditionally use to cover the content that appears in the project; or helpful new websites and activities to cover contemporary topics.

Again—backwards planning—I zoom out and look at the big picture before zooming in to look at the specific days. I first map out approximately how long each benchmark will take me (typically 1-2 weeks) and then I go into each day and think about specific lessons within each benchmark. I then will drill down to think about differentiation within each day. Check out the companion site to Keep it Real with PBL for sample calendars, resources on differentiation and project management.

After spending a great deal of time working in PBL organizations, and writing my dissertation on PBL as a pedagogy in practice, I landed on this flow for project planning because I think it simplified a process that can often become larger than life for teachers. It’s my hope that by embedding standards, best practices of UBD and formative assessment that teachers will begin to see how PBL can be a helpful framework for them to teach what they need to cover, without it feeling like one more thing to do!

You can learn more from Jenny at her website, CraftED Curriculum. This entire lesson is detailed in her book, Keep it Real with PBL: Elementary.

And if you’re a secondary teacher, check out her book, Keep it Real with PBL: Secondary.

Come back for more.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.