Robust strategies typically incorporate multiple trade-offs. The very best have trade-offs at almost every step in the value chain.

Consider IKEA, the Swedish home furnishings giant. IKEA’s value proposition is to provide good design and function at a low price. Its target customer is what IKEA calls the person “with a thin wallet.” In choosing its particular kind of value and the activities needed to deliver it, IKEA has accepted a set of limits: it does not meet all the needs of all customers.

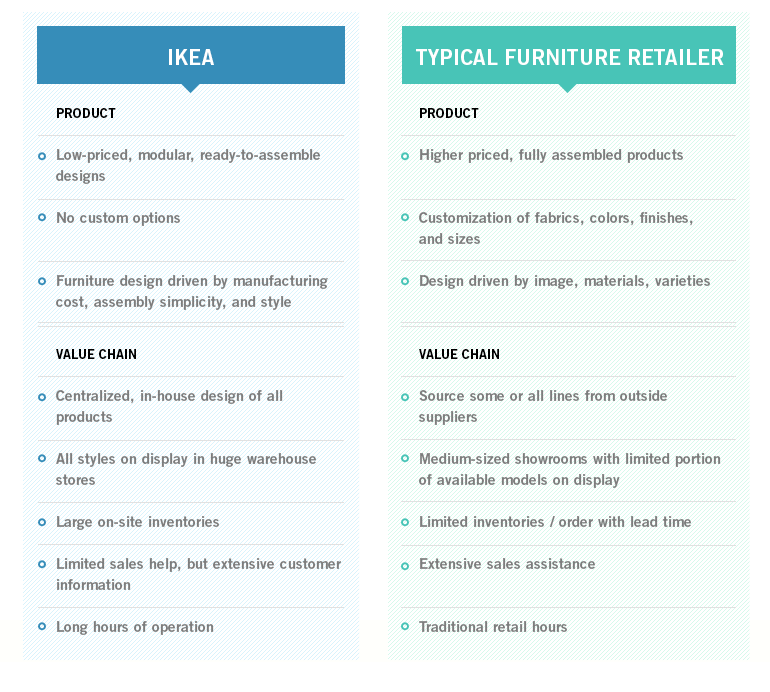

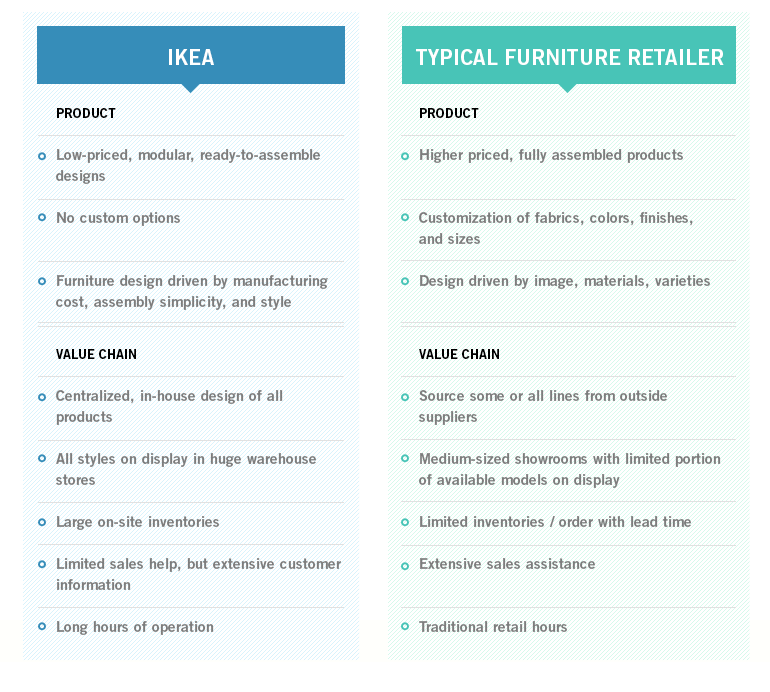

In every major value-adding step in the process of creating and selling home furnishing, IKEA has made different choices from the “traditional” home furnishings retailer.

A strategic position is not sustainable unless there are trade-offs with other positions. Trade-offs occur when activities are incompatible. Simply put, a trade-off means that more of one thing necessitates less of another. An airline can choose to serve meals—adding cost and slowing turnaround time at the gate—or it can choose not to, but it cannot do both without bearing major inefficiencies.

Trade-offs arise for a number of reasons. Porter highlights three.

First, product features may be incompatible. That is, the product that best meets one set of needs performs poorly in addressing others. S econd, there may be trade-offs in activities themselves. In other words, the configuration of activities that best delivers one kind of value cannot equally well deliver another. Another source of trade-offs is inconsistencies in image or reputation.

Trade-offs are pervasive in competition and essential to strategy. They create the need for choice and protect against repositioners and straddlers.